- Home

- Hawes, Sharon;

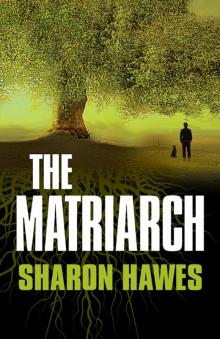

The Matriarch Page 7

The Matriarch Read online

Page 7

“Couldn’t it be said,” Charlotte says, “that this same fig leaf actually fought sin? Didn’t the leaf cover the genitals to protect the viewer from lust?”

“Well … I guess you could make that case all right enough,” Dott says.

Frank sets out the whiskey, and I pour a generous ration into my coffee. I’m thinking about Frank’s take on Charlotte and Dott and remembering the kiss at The Tree. Charlotte had kissed me. I know I didn’t misread her enthusiasm.

“Your question, Cassidy,” Franks says, “about there being more than one type of fig on the same tree—I don’t think that’s likely. But what do you think, Dott?” He picks up the whiskey bottle and empties it into his coffee cup. I think he’s been sucking down the Dickel pretty good ever since Carla took a swing at him with her purse. “There’s another bottle in the cupboard, Sweetie,” Frank says to Charlotte.

“The fig is one crazy tree,” Dott says. “It’s got some mighty strange habits. I guess the trees could swap types if a couple different varieties were growing close to each other. Like in the rain forest.”

“Not here, I guess,” Frank says. “But my tree …”

Charlotte pours more coffee into his cup. I’m relieved to see that she’s neglected to bring out the fresh bottle of whiskey.

“What do you think about that, Dott?” I ask. “About Frank’s tree growing all those varieties? That’s damned unusual, isn’t it?”

She’s silent, frowning. Then, “I honestly … don’t know.”

“So, Dott, you’re a preacher?” Charlotte asks.

Dott nods.

“Where?” Charlotte sits down and I imagine her denim skirt creeping up onto her tan thighs.

“In that big tent at the southern edge of town. I can’t make a living out of preaching of course, so I’m looking for work. The church lets me stay in their tent, which is a big help. I’m saving up for my next Quest. In Crete.”

“Crete,” Charlotte murmurs. “How lovely.”

“I am blessed,” Dott says.

I look over at Frank and see him nodding off in his chair, his coffee mug about to fall. I lean across the table, gently take the mug from his hand, and place it on the table.

“What denomination is your church?” Charlotte asks.

“None. No real denomination.” She leans forward. “The church tent is a traveler, one of those sturdy semi-permanent types. We reach the rural masses.” She smiles a maternal, caring smile, and at that moment she’s almost lovely. “I preach there Saturday and Sunday nights. I’d be real pleased to see you there, Charlotte. You too, Cassidy, if you’d like.” She gathers her mug into a giant hand and takes a swallow. “There are several preachers in our church. Each can stand and speak about whatever’s on his mind. The evil in the world or the good. There’s no set doctrine. We just let it all hang out, and when we’re through, we’re at peace. Simple, huh?”

Maybe it’s the home-cooked meal. Or Charlotte’s kiss. Or maybe it’s the simple act of returning to the place I once knew as home, but I feel good. At peace. A simple feeling, yet so difficult to achieve. It’s foreign to me. But I like it, and I hope it will continue.

“Evil in the world,” Charlotte says. “You mean like the devil? Does your church believe in the devil?”

Dott hugs her coffee mug to her chest. “People argue, you know, about the devil, about the existence of evil.”

She pauses, and I hope this topic will turn out to be riveting, because I’m so lulled by food I have trouble focusing on her words. She moves her chair back and rises. She walks to the stove and turns to face us—Charlotte, the dozing Frank, and me. This woman must be well over two hundred pounds, I think as I study her. Those pounds of solid female flesh, bursting with robust good health. Dott’s tee shirt reveals an ample bosom and well-muscled arms. Her tight shorts cling to thick tanned thighs, and she wears high-topped leather hiking boots. She makes a hell of an impression just by standing up.

Frank is dozing, but not really. Sometime ago, he discovered one of the handy ruses of the elderly—the fake nap. Unlike the presence of a hearing problem, where he would have to put up with harsh shouts, Frank simply closes his eyes and relaxes his body. He finds this to be wonderfully refreshing and acceptable—a mere timeout, so to speak. Sometimes he does indeed drop off for a short nap, but usually he just indulges in restful eavesdropping.

“Shall I tell you of my education in evil?” Dott asks. Frank hears everyone shift about in their chairs as they settle in to hear Dott’s story.

“I was young, almost fourteen, when I saw a man grow horns. They came bursting out of his forehead just like in a cartoon. I was standing in line to see a movie, and he cut into the line in front of my friend Rebecca and me.

“You’re cutting in!” I said to him, and he turned to stare at us. That’s when he grew the horns. And his eyes changed. They shrunk down to small mean eyes, kind of savage-like.”

“He was looking at you?” Frank hears Cassidy ask.

Sweet baby Jesus! Is the boy buying this garbage?

“No, at Rebecca.”

“What on earth …” Charlotte says softly.

“That’s my point,” Dott cries. “He wasn’t of this earth. The man had become evil right before my eyes!”

Her voice is dramatic and forceful, and Frank reminds himself that this woman is a tent-house preacher and not to be taken seriously. How did she become a self-ordained, whacko-preacher and a homosexual one at that? A story there, Frank is thinking, but he doesn’t care to hear it.

“So, what did you do?” Charlotte asks.

Dott sighs, and Frank hears her clomp over to the table and sit back down. “I was just a girl, you know? Here was a demon standing right in front of me. I thought I had lost my mind for sure. I looked over at Rebecca who was staring down into her Coke; I wasn’t sure she had seen the bad guy arrive. I took another peek then, and the demon was gone. The man was glaring at me, but he was just a man.

“I decided I couldn’t really have seen what I thought I had. It was simply not possible. I did my best then to forget the whole thing.”

And high time too, Frank is thinking. Talk about imagination!

“About three months later, Becca and I got to talking, and I told her what I thought I’d seen. She told me she had seen it, too. She swore to me she saw that man grow horns and turn into a demon right in front of us! Becca said she didn’t say anything at the time because she thought she was losing her mind.”

“So, what did you do?” Charlotte asks.

“Nothing. What was there to do? The church would probably explain our story away with some kind of mumbo jumbo and treat us like idiots. We did nothing. We didn’t tell anyone about it either.

“To answer your question, Charlotte,” Dott goes on in a low, serious voice, “yes, I do think there’s evil in the world, and maybe even a demon or two.”

“Bullshit,” Frank says, unable to keep still any longer. “That devil stuff is pure crap.”

Dott smiles at him. “Maybe so, Frank. I’m simply telling you my experience with a man I saw as evil.”

Frank looks over at Cassidy who appears confused but is smiling at the two women. He sees a flash of light outside, and Louie shoots out from under the table, barking.

I hear a car door slam, followed by the sound of someone climbing the porch stairs. I get to my feet just as that someone raps on the screen door. Louie starts for the door, and I follow him. At the door stands a sweating, chunky man in the tan and navy uniform of the sheriff’s department. I grab Louie by his collar. The man has a fading athletic build, and his gut suggests a fondness for beer.

“Mr. Murphy in?”

Frank arrives at the door. “Manny? That you? Oh, Al.” He sounds disappointed as he pushes the screen door open and waves the man in. They shake hands. “This here’s my nephew, Cassidy. Deputy Smith, Cassidy.”

“That’s Schmidt,” the deputy says. He flashes Frank an irritated look. He takes his hat off and

inclines his head toward me. Deputy Schmidt has sun-streaked hair cut short and close to his head, almost like a helmet. I see a white scar that plunges down his tanned forehead to join the deep frown line between his ice-blue eyes. “I’m the acting sheriff now,” he says. “While Manny is down with the flu. Albert D. Schmidt.” He extends his hand, and I take it.

“Hello, Al,” I say, smiling. Louie growls, low in his throat. “Sit,” I say, and the pup complies.

A picture comes into my head: friends sharing this summer evening together—normal, peaceful, benign. This idyllic scene hangs in my mind, suspended in time for a brief moment. Somehow I know, as Albert D. Schmidt takes a breath to speak, that picture is going to change. It has already changed.

“Manny wanted me to stop by,” the deputy says. “He figured you being such good friends with the Russos.” He makes a show of shuffling his feet and fiddling with his hat.

Louie growls again; he knows a phony when he sees one. Whatever this asshole is going to say, both Louie and I know his emotion is less than sincere.

“Mr. Russo …” the deputy says, “he was killed earlier tonight. Murdered.”

I’m silent, stunned.

The kitchen door is open, I hear a cell phone ring, and see Charlotte pull her phone from her pocket and put it to her ear. Dott is staring at us, motionless.

As Charlotte murmurs into her phone, the deputy is scanning Dott and us as if waiting for his words to register. He seems to grow taller—to actually loom—and the corners of his mouth turn up ever so slightly.

“How could that happen?” I ask.

“Well, it looks like his wife did it,” Deputy Albert says. “She called it in. Looks like the little lady hacked him to death with a meat cleaver.”

I hear Uncle Frank gasp and see him slump to the floor.

“You could have softened that, Chrissake,” I say as I kneel to my uncle. “Hacked? ‘The little lady hacked him to death?’ Real thoughtful choice of words there, Al.”

“You asked me, didn’t you?” The deputy’s face flushes red. “You don’t wanna know, don’t ask.”

I rise, one hand on Louie’s collar, while the other forms a fist.

“Whoa there, Cass,” Dott cries, hurrying over to us. She puts a big hand on my arm. “We’ve got to see to Frank.” She slides a firm arm around my waist, and I hold myself rigid, aching to belt this smug lawman.

Dott crouches and puts her fingers to Frank’s throat, feeling for his pulse.

“He okay?” I ask, beginning to be ashamed that I’d rather deck Deputy Al than help my uncle.

She nods. “Pulse is strong. He’s coming around.”

Charlotte rushes through the room toward the front door. “I’m out of here,” she says, clutching her phone. “Shelly’s alone at the Russos’ house. The police have taken Carla into custody.”

I move toward her. “I’ll call you later,” I say, and she nods as she runs out the door.

“Cassidy?” Frank says with his eyes wide open. He looks scared.

“I’m right here, Uncle Frank.” I kneel, taking his hand.

“Help me up, boy.” I pull him up into a sitting position. Dott brings him a glass of water, and he drinks it down. He looks over at the deputy. “It’s true?”

Louie goes to Frank and licks the old man’s face.

“Yes sir,” Deputy Al says. “I’m … real sorry.” After a moment, his gaze goes to my face. “That your Ranger out there?”

“Yeah.”

“I need to talk to you.” He steps to the door and motions me to follow.

“I’ll be right back, Uncle Frank.” I walk out onto the porch with Schmidt.

“What kind of dog is that?” he asks.

“American Staff Terrier.”

“Isn’t that the same thing as a Pit Bull?”

“He’s an American Staff Terrier,” I say. “You bring me out here to ask about my dog?”

Al looks toward the Ranger. “Your registration has expired,” he says. He’s smiling.

“What?”

“Your regis—”

“Yeah, well. I’ll take care of it.”

Now? You choose this moment to tell me about that?

“Thanks for the reminder.”

“No reminder,” the deputy says, favoring me with a grin. “I have to write you a ticket.”

“Al, for Chrissake,” I begin, but I know this fucker is getting off, and happy as hell to write me a ticket.

“No problem, Cassidy,” Al says with a wave of his hand. “You stay with your uncle. I’ll leave the ticket on your windshield.” He puts his hat on, gives me a mock salute, and goes down the stairs.

With Dott’s help, I get Frank into his bed. He lies on his back, his hands across his chest. He’s hugging himself. I see him shiver and pull the covers up over his arms to his chin. A role reversal, I’m thinking. How many times had Frank put me to bed when I was little? I always wanted the blanket tucked in on both sides holding my arms and legs down, the tighter the better. I’d felt safe that way, as if strapped into security.

Dott and I stand at Frank’s bedside watching him drop off to sleep almost instantly. We tiptoe out of the room and walk together to the front door.

“I’ll be happy to stay if you think I can be of help.” She swipes at her hair with a hand.

“Thanks, but I think he’ll be okay now—at least for the night. C’mon, let’s sit outside for a moment.” We go out onto the porch with Louie and settle into the wicker chairs at the table. The night is moonless but bright with stars. The serene beauty of it makes me uneasy, as if it’s hiding a menace I can’t begin to name. And I don’t blame my anxiety totally on the disturbing murder of Dante Russo. There’s something more going on here … but I haven’t a clue.

“You knew the Russos?” I ask Dott.

“Not well. They seemed happy enough to me. But marriage is a trip into the mystic unknown as far as I’m concerned.”

“I need to ask you …” I laugh, knowing my questions will sound weird. “This is going to sound fucking crazy—” I stop, realizing I’m speaking to her as if she’s male, one of the guys. “Excuse my language, Dott; I do apologize.”

Dott gives a snort and whacks me on my back. “Don’t be ridiculous.”

“I need to ask you about fig trees. You seem to know a lot about them. Have you seen Frank’s tree?”

“Not for a long time, I guess. Not since well before the quake. It was a little bit of a thing back then, a scrub.”

“See, that’s part of the puzzle,” I say. I think for a moment, and Dott is silent, waiting for me to explain. “Frank told me that tree’s been almost barren for years, no fruit to speak of. Then the quake hits, and all of a sudden The Tree grows big time. And it’s producing so many figs and so many different types … Isn’t that abnormal?”

I fish a cigarette out of my shirt pocket. Dott picks up the box of wooden matches and removes one. She strikes it and guides the flame to my cigarette. Her gesture is graceful and natural, as if she’s preformed this somehow intimate courtesy many times before. Her face glows in the brief flicker of the match.

“I mean, it’s only been around nine months since the quake,” I say, still unsure of my take on The Tree. “Frank says, like you Dott, that it’s been just a scrub with practically no fruit. But Charlotte and I were just out there, and it’s sure no scrub now. How could an earthquake make that kind of difference? What could it possibly do?”

Dott laughs and gives me another whack on my back. “Hell’s fire, Cassidy, it’s not that unlikely.”

Her loud voice resounds in the quiet night, and I find it a relief, as if she can blow my misgivings away with mere volume.

As a boy lying in bed at night, I could hear my dad and Uncle Frank in the living room shouting at each other after too much dinner and drink. But I would easily drift off to sleep because of the laughter mixed in with those raucous voices. I felt buffered from the world—protected by those loud, boisterous men.

“The change in growth could happen,” Dott goes on. “A sudden influx of water, maybe. You spend any time in a rain forest and you see just what’s possible in the way of growth. And it can be damned weird growth!”

“But, Dott,” I say quietly, my sense of comfort vanishing, “we don’t live in a rain forest. This is Southern California; it’s almost a desert.” I pause and wonder how to phrase what I want to say without sounding like a city boy spooked by no-frills life in the country. “Earlier today, I fell against the trunk of that tree and knocked myself out.” I decide to leave out the part where I was going to fire my new handgun up into the branches. “When I came to, I could swear …” But I can’t do it. I can’t tell Dott that The Tree has skin and breathes.

It breathes!

I search my mind for something more reasonable I can swear to. “I swear that trunk is not wood.”

“So,” Dott asks in a patient reasonable voice, “what is it?”

“It’s a pale green, almost skin-like.” I close my eyes and lean back in my chair. “Shit, Dott, I don’t know what it is.”

“It’s wood, Cassidy, tree wood, or maybe a big vine. A lot of trees have big, stem-like trunks.” She pauses. “Are you thinking about this in relation to my story earlier? About that demon?”

“No, not at all,” I say, surprised at the question. That story had seemed like pure nonsense to me.

“Do you think the tree is evil, Cassidy?”

Her eyes burn into mine. Evil. I have to think about that one.

That tree scared the shit out of me today with its obscene glut of figs, its skin-like trunk, and the fact that I can practically see it grow. And then there’s the breathing. My uncle rambles on about something dark in the air since the quake, and then comes the news that a kind, loving woman has apparently butchered her husband like a piece of meat. I want you to explain all this to me Dott, and then I want you to make it all go away.

But I don’t say any of that to her; I don’t want her to run screaming off the porch and leave me all alone. I laugh instead and stub my cigarette out. I reach over and take Dott’s hand in both of mine. “Hey Dott, it’s been a crazy day, you know? Crazy murder, crazy tree—I don’t know what I think.” I grin and release her hand. “I’ll walk you to your truck, Dott.”

The Matriarch

The Matriarch